Blog Archives

My Favourite Albums of 2019: The Top Ten

Goodbye, 2010s

Whittling a list like this down to a top ten is a ridiculous challenge, and after all that time bashing, tinkering, and cobbling together something vaguely satisfying, a side effect can be a confused perspective quality-wise. Yes, these are my favourite albums of 2019 (at time of writing, anyway), but serious jewels abound elsewhere in the year’s offerings. May we continue to honour them all with close listening and shared praise long into the future.

Speaking of those other great albums, if you’ve skipped ahead to this Top Ten without first reading Part I, shame on you. Helpfully, you can amend that here; otherwise, pop some headphones on and enjoy this highly subjective but very earnest countdown!

(This article contains a lot of F-bombs, not all of them Lana Del Rey’s fault. You’ve been warned.)

10

The Comet is Coming

Trust in the Lifeforce of the Deep Mystery

Apocalyptic drama! Virtuoso telepathy! Crazy cosmic jazz! Trust in the Lifeforce of the Deep Mystery is a frantic hurtle through psychedelic jazz charged with end-of-the-world urgency. The sounds are still molten, glowing with the heat of impassioned and incantatory playing captured at full tilt. It’s only the second full-length release from the trio (Shabaka Hutchings, Dan Leavers and Max Hallett), but all are dedicated careerists in the pursuit of art, and their bloody-minded focus on tapping into the most intense and intoxicating sounds possible can be heard at every moment.

The album is densely packed and tonally oppressive, but it’s also completely addicting. Boasting titles like ‘Birth of Creation’, ‘Super Zodiac’ and ‘The Universe Wakes Up’, Trust in the Lifeforce… has lofty ambitions, and rises to meet them from the get-go. ‘Because the End is Really the Beginning’ is an eye-widening, horizon-broadening opener, all thundering percussion, pained synths and doomy ambience, but the listening experience is leavened by the thrill of witnessing three exceptional players locking in and effortlessly taking flight.

Trust in the Lifeforce… is colossal with ecstatic dread, but the real damnation is doled out not by celestial or natural disaster, but by ourselves. Looming at the album’s centre is ‘Blood of the Past’, a cut which surfs a thick, treacly bass line under a hail of Hutchings’ furious blasts, the typhoon only subsiding to allow a star turn from Kate Tempest. Her verse gives politically and socially charged bite to the album, and recontextualises the apocalyptic sonics at work. For The Comet is Coming, cosmic danger and wonder is one thing, but humanity’s potential for both salvation and self-destruction is what’s really worth railing against, and they give it with both barrels on this exhausting, exhilarating record.

“It will not be stilled / It is there in the air.”

9

Purple Mountains

Purple Mountains

The last recorded dispatch from David Berman is wrenchingly sad, richly melodic, and deceptively simple on the ears. The plainspoken clarity of its arrangements, and the dreary delivery of its lyrics could seem reductive in some hands, but Berman imbues all with an earnestness that shines through even his most acidic wordplay. Yes, there’s scornful humour and self-effacement, but the authenticity of the material’s raw origins is beyond doubt. Purple Mountains reckons with the relentlessness of depression, the alienation of exiting a significant relationship, and the hardship of justifying one’s existence in a world that may be beyond redemption.

The sources are bleak but the results are beautiful, the unfussy but tasteful instrumentals taking the biting pain behind Berman’s morose countenance and elevating it skyward. The aching ‘Darkness and Cold’ should sound sulky, embittered and entitled, and to a degree, it is. But at its heart, Berman locates all-too-human reserves of feeling, as he does on all songs here. The tragicomic mundanity of growing older, losing touch, and being helpless to break self-destructive cycles is laid bare by Berman (“lately I seem to make strangers wherever I go”), his words cossetted by low-key Americana redolent of 1970s soul-bearers. Every line is a quiet masterclass in refined incision.

We should be careful in placing a distinctly male form of suffering on a pedestal, especially when such polemics are layered with privilege. But on his final album, Berman identified incredibly resonant weaknesses and neuroses while poring over his personal troubles, and chose to broadcast a final empathetic message to his fans, shirking the syrup of self-help doctrines in favour of gallows humour and droll weariness. It hurts to know that he ultimately chose to silence his demons with the permanent solution, but he nevertheless chose to release Purple Mountains for what it is: a way to connect with his listeners once more, and offer a little more unity, solace, and understanding in times of darkness.

“The end of all wanting is all I’ve been wanting.”

8

Richard Dawson

2020

Richard Dawson’s follow-up to Peasant turns its gaze from the medieval age to the immediate future, assimilating the chaos and divisions of modern Britain into nine brilliant and diverse first-person tales. Dawson’s bardic writing is perfectly suited to his extraordinarily commanding voice, the bray of a town crier capable of acrobatic leaps in pitch and tone, and the unusual, jagged instrumentals (which were almost entirely performed by Dawson himself) are frequently breathtaking. The songs are rooted in quotidian trials and tribulations of UK citizens, packed with incidental detail that augments the humour and the gloom alike. A heart emoji appearing on a smartphone screen sets in motion a sequence of violent intent. An employee at an Amazon fulfilment centre struggles through the daily horror and indignity of inhuman working conditions. A homeless person taking shelter in a pedestrian tunnel is terrorised by passing football fans.

It’s true that these songs are dominated by grim tidings, but as on Peasant, Dawson places his emphasis firmly on the characters central and peripheral to the issues at hand, letting them work within three dimensions rather than filling the album with his own sloganeering. He treats his characters not with irony or scepticism, but instead allows them to feel and report everything in their own voices, letting the contrasting opinions and emotions clash. A father-son relationship is tested during a football match in ‘Two Halves’, shifting from masculine rage (“stop fannying around! Keep it nice and simple / You’re not Lionel Messi!”) to a weird reconciliation of sorts over the choice of a takeaway dinner. On ‘The Queen’s Head’, a butcher gives out supplies to villagers when a nearby river bursts its banks, while vocally scapegoating “benefit-scrounging immigrants” for the lack of adequate flood defences. On ‘Jogging’, a man senses disarray and criticism on all sides, but clings to the exercise ritual that dependably gives him a daily sense of purpose. It’s an impressive array of voices, not all of them agreeable or even morally palatable, but all ring with authenticity, and are presented without snobbery. Dawson’s powers of observation are remarkable, and throughout 2020, his songwriting reaches fresh peaks.

“How little we are in the mouth of the world / Come hell or high water, how little we are.”

7

Little Simz

GREY Area

I was very late to Little Simz. My first listen to GREY Area was my first listen to any of her output, but her latest album is nailed so effortlessly, I made up for the lost time with compulsive repeated spins. Co-written with enigmatic producer (and schoolmate) Inflo, Little Simz (aka Simbiatu Abisola Abiola Ajikawo) doesn’t waste a moment, racing through a breathless set of smart, sharp and shocking tunes based around navigating the wilderness (the “grey area”) of one’s twenties. Specifically, navigating one’s twenties in an industry of box-ticking drudgery, in a country of persistently ugly social politics, in a world where hopes for the future continue to dwindle at an alarming rate. Ajikawo has no shortage of things to say, and she does so over simple but impressively varied instrumentals, from scuzzy, swaggering hip hop to dreamy, lo-fi soul. One common denominator? They’re all strikingly catchy.

Ajikawo has already cut her teeth on multitudinous mixtapes, EPs, and two previous albums, as well as a number of guest features with an increasingly impressive roster of fellow artists. Now aged 25, she’s already accommodating the likes of Little Dragon and Michael Kiwanuka on belters of her own. Such confidence, dogged focus, and quickly-accrued experience isn’t always a guarantee of excellence to come, but GREY Area doesn’t put a foot wrong. Ajikawo’s flows are dextrous, her writing bracingly honest, and her messages by turns relatable and respectable. It’s often both, as even if her own experiences aren’t shared by the listener, the emotional whirlwinds they catalyse are transmitted with fierce clarity. On the likes of ‘Boss’ and ‘Venom’, Little Simz dares her listener to underestimate her at their own peril, but it’s hard to imagine anyone still in need of convincing based on this material.

“I know it’s material, but not irrelevant / All this here is worked for, not inherited.”

6

Joan Shelley

Like the River Loves the Sea

Few artists have captured the appeal of their own albums so succinctly as Joan Shelley in her personal summary of her fifth album, which she refers to as “a haven for overstimulated minds in troubled times”. Decamping to Reykjavik to record seemed to blow fresh breezes through Shelley’s creative landscapes, and the songs borne by the sessions sound as light as air, mostly built on little more than her voice and uncommonly pretty fretwork. There’s little need to adorn them further, as Shelley’s abilities as guitarist and singer are beyond doubt. Her voice is a miraculous thing: warm, companionable, and clear as a bell. There are no dramatic flourishes to speak of; the closest Like a River… gets to a crescendo are the cascading harmonies that lift the heavenly ‘High on the Mountain’ to a new level. The ambience is exquisite, and moments of loveliness abound: ‘When What It Is’ drifts on cloudy, spectral pianos, ‘Teal’ makes a gentle paean to autumnal fragrance, Shelley holds her friends close and marvels at the natural world on the folky sway of ‘The Fading’.

Shelley’s gaze roves over the bubbling landscapes of Iceland, the steadily expanding stretch of sea that seperates America from Europe, and fixes her sights on her place of home and comfort: Kentucky, where it’s always five years behind. “You have to leave home to see what it is, to frame it neatly,” she writes. “To miss a thing is to know its shape.” In its idyllic sound, Like the River… does indeed succeed as a haven for overstimulated minds, but not one which merely anaesthetises. This is music of grace and generosity, and consistently brings me back to ground, setting me standing a little straighter, a little more fortified.

“That’s where I’ll be when the seas rise / Holding my dear friends and drinking wine.”

5

Lana Del Rey

Norman Fucking Rockwell!

Norman Fucking Rockwell! is the apotheosis of Lana Del Rey’s established rules and rites; a work that takes all that came before, and finds a way forward that honours and utilises the lessons learned over a decade in the game. It’s a great stride forward for Del Rey as a songwriter, rooted not in stylistic revolution but a growth in and refinement of her hallmarks, and certainly, this is her strongest and most beautifully packaged sequence of songs yet. Jack Antonoff strips away any remnants of gaudy pastiche in her instrumentals, allowing the bare-bones strength of Del Rey’s songwriting to take the spotlight. The gauzy and elegiac mode favoured here is lovely on the ears, and makes for a supremely effective pairing with Del Rey’s swoons over a tarnished American Dream. Such a glamorous fantasy continues to appeal and fascinate, but Del Rey struggles to square it with modern reality: climate crises, the rise of the alt-right, ritual silencing, toxic masculinity run riot, and heroes falling on all sides (take your pick: death or “blond and gone”).

This tension unites the fourteen songs of Norman Fucking Rockwell!, and though it’s a dense and expansive listen, highlights come thick and fast. ‘Mariners Apartment Complex’ makes an early bid for the best song Del Rey has yet released, a towering peak of dramatic balladry that bites at critics (“they mistook my kindness for weakness”) and doubles down on her decisions in life and love with flinty tenacity. It’s exceptional, but is usurped when ‘The greatest’ bowls in to commence the album’s final leg: a fuzzy, slow-motion firework of yearning soft-rock and a piercingly incisive cry from someone who can see the Big One approaching. The allure and toxicity of the West Coast is declared in rapturous verse as Del Rey throws herself into one final dance before the flames take hold.

By the curtain call, Del Rey is at her most hushed and potent, as darkness draws in on all sides. It’s now 2020, and it may already be too late to save anything, but Lana Del Rey gives enthralling voice to these final radiant glimmers of hope before the old dreams die for good. And it’s a fucking stunner. Goddamn, indeed.

“And who I am is a big-time believer / That people can change.”

4

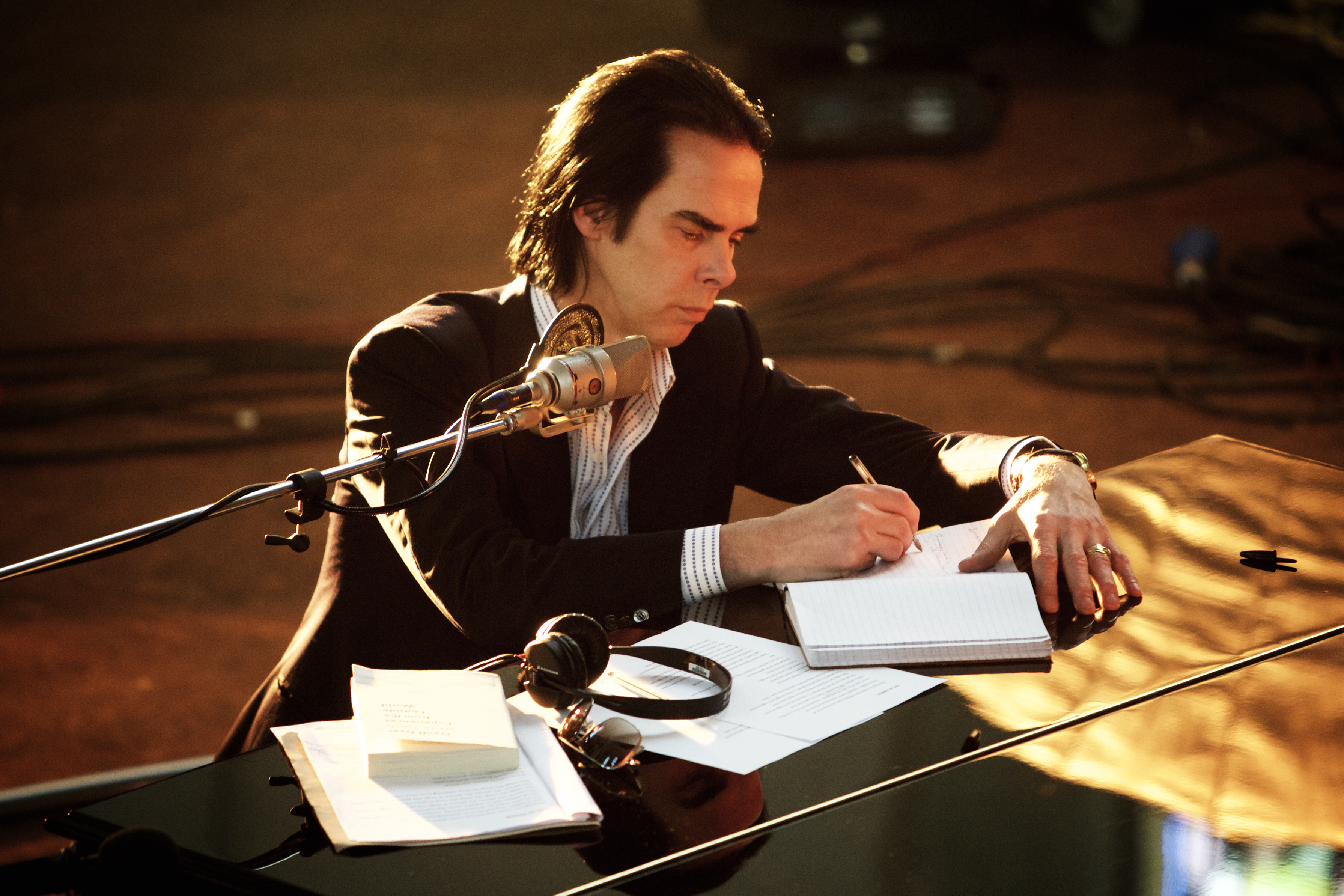

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds

Ghosteen

The first time I tried listening to Ghosteen, I only lasted for three minutes before I had to stop, because it was already too painful to hear. Though ‘Spinning Song’ (and its parent album) is awash with peculiar imagery and dreamlike non-sequiturs, couched within the fablelike stories of galleon ships, prowling predators and Elvis Presley are moments in which Cave cuts straight through the atmospherics and reveals – in a voice that has rarely sounded so nakedly affected – the depths of the grief roiling inside him. In interviews, Cave has identified the “Ghosteen” of the album as a migrating spirit, and the tragic death of Cave’s son Arthur reverberates through and binds these eleven songs, the trauma painfully felt in moments such as the crowning sentiment of ‘Spinning Song’, when Cave breaks into the repeated utterance “and I love you”.

These capsules of direct mourning pepper the strange and impressionistic tales Cave spins throughout Ghosteen, and things don’t get any easier to bear – nor any simpler to parse – for the full duration. But what a monumental experience it offers. Adrift on woozy and largely drum-free instrumentals spearheaded by Warren Ellis, these songs mirror the taut emotions and cerebral disarray of Cave’s words. The unabashedly elegiac qualities aren’t for everyone, and even established Cave fans have not warmed to Ghosteen in its lengthy, mournful dimensions. But by my reckoning, this is one of the decade’s most touching albums, concealing real poetry within its heavy drones, menacing electronics, clangourous bells and choral vocals.

And at its most powerful, Ghosteen is peerless. ‘Bright Horses’ is simply one of the most beautiful songs of Nick Cave’s career. Every element contained within it clutches at the heart, from its funereal piano motif to the lonely angelic falsetto that drifts in and out of earshot. The closing third brings me to tears on every listen; Cave stood on a train platform and insisting in an impassioned whisper that he can hear his baby returning to him. “The world is plain to see,” he intones, his voice cracking with wonder, “it don’t mean we can’t believe in something.” It’s one of the saddest and most beautiful things I’ve ever heard, and it cuts right through me. A deeply stirring, haunting and comforting piece of work on a deeply stirring, haunting, and comforting album.

“Everything is as distant as the stars / I am here and you are where you are.”

3

Aldous Harding

Designer

Aldous Harding’s third album seems unassuming enough at first. Clear, folksy, neatly arranged melodies snake around one another with plenty of space to breathe. Nylon strings flutter and twang, piano keys gleefully announce themselves at unexpected moments, horns settle lazily in the background, and at the centre of it all, Aldous Harding’s shapeshifting voice intones peculiar phrases such as “you bend my day at the knee” and “what am I doing in Dubai?” Idle listeners could be forgiven for merely considering it “pretty”. But surely and stealthily, it begins to work its magic, repeated listens revealing the strength of the hooks and the tenacity of Harding’s puzzling wordplay. Her voice is extraordinarily adaptable, shifting from sing-song falsetto (‘Zoo Eyes’) to gravely deep (‘Damn’) and everything in-between, each syllable released carefully and with exacting emphasis.

A shroud of darkness falls after Designer’s stellar first half, but Harding is so chameleonic that the album doesn’t lag after the set change. It beguiles with its plays of light and shadow, and its most spellbinding moments are its quietest: the tender (and bewitchingly creepy) ‘Treasure’ is a real gem, as is the sad, bizarre ‘Heaven is Empty’. But Designer is also a hugely enjoyable work to behold: the cryptic childbearing riddle of ‘The Barrel’ (check out its essential video of grotesque masks and joyous dancing) is outstandingly catchy, and the bouncy jam on the title track absolutely slaps. Enrapturing like little else this year, Designer continues to pull me into its appealing, unsettling world over and over again, and I’m very content to let that continue for years to come.

“The wave of love is a transient hurt.”

2

Jake Xerxes Fussell

Out of Sight

Reading the liner notes of Out of Sight is like being presented with a musical treasure map. The nine songs lining the third album of majestically-monikered Jake Xerxes Fussell have an impressive span, from market trader chants (‘The River St. Johns’) to upcycled Irish folk (‘Michael Was Hearty’), music hall waltzes (‘Jubilee’) and 1800s Celtic balladry (‘Three Ravens’), all of which are exceptionally well-renewed, and equally well-performed. Fussell has made his name by exhuming traditional arrangements, dusting them down and adding his own flourishes, and with a full band now on hand to tease out the magic of these songs, Out of Sight is his most captivating collection yet.

The drive of exhuming such musical artefacts isn’t empty nostalgia, but a reverential carrying of the torch, locating the traditional purposes of storytelling in folk music, and allowing these words and tunes to travel further still. Out of Sight is a graceful doff of the cap to the songs and histories thereof that exist on the peripheries of cultural memory, and it happens to be a delightful listen in its own right. The album is brimful with gorgeous melodies, and some inventive tweaks to the originals result in moments of pure bliss. Early highlight ‘Michael Was Hearty’ achieves a sense of weightlessness between the drum patterns anchoring it; ‘The Rainbow Willow’ loops around a lovely, lilting instrumental, and the piano that plonks through ‘Drinking of the Wine’ exemplifies the comradely swing of all gone before. This is a charming album, witty, coherent, and seldom short of beautiful.

“High was the step in the jig that he sprung.”

1

Weyes Blood

Titanic Rising

Is Titanic Rising a masterpiece? It’s very early to tell, but I think it could be, and at the very least, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better-sounding offering from the past year, even considering the baseline calibre of the class of 2019. By my estimation, no other musical package was so sumptuously presented in every aspect. The songwriting, the arrangements, the performances, the lyrics, the production, the artwork, the sequencing… Titanic Rising is so immaculately and impressively assembled, it’s impossible to miss the quality of effort ringing through it from start to finish. Everything gels, and the result is a thing of extraordinary beauty and staying power.

Natalie Mering has progressively come into her own as a gifted songwriter, attuned to the micro and macro of her ongoing body of work. On Titanic Rising, she seamlessly incorporates her inspirations into a collection of diverse songs which sound resolutely unified. Chamber- and baroque-pop, sun-dappled ’60s harmonies, Laurel Canyon balladry, moody synth-rock, and a patient croon that draws from the Karen Carpenter playbook all cohere wonderfully with Mering at the tiller, evoking a spotless vintage feel while dealing with very contemporary lyrical concerns. The climate emergency, an impossible yearning for lost innocence, West Coast dissonance, the terrible beauty of unattainable standards, and good old dependable heartbreak are all given voice, and are sculpted into beautiful shapes by Mering and co-producer Jonathan Rado. Running through the tracklist is like naming one freshly dredged classic after another: ‘A Lot’s Gonna Change’, ‘Andromeda’, ‘Everyday’, ‘Something to Believe’ – each sets a high bar for the competition, and that’s just the opening stretch.

Mering’s childhood bedroom was painstakingly recreated and then completely submerged for the album’s staggering cover, both tying into the blockbuster infatuation she espouses on the staggering ‘Movies’, as well as hinting at the vast depths of detail and feeling beneath the pristine surfaces. Behind each handsome melody is a world of emotional disarray and nuance, a thumping heartbeat which is never lost, even in the album’s headiest moments. ‘Andromeda’ reaches for connection amid technological and environmental catastrophe, its weeping slide guitar and quavering wash of keys amplifying the ache behind Mering’s guarded plea “if you think you can save me / I dare you to try”. ‘Picture Me Better’ is perfectly composed but rife with gut-punches on closer inspection, written for a friend who took their own life while the album was being written. Even after countless listens, these songs find their way to the heart, continuing to utterly captivate in form and in content.

I would say that when this album soars, it truly soars, but it never once settles for anything less. When the stately strings of ‘Nearer to Thee’ summon Titanic Rising to a close, recalling the eerie opening melody of ‘A Lot’s Gonna Change’, it’s the most handsome invitation imaginable to take the journey once again. Not that you need further encouragement by that point: on Titanic Rising, Weyes Blood immerse the listener in a world of treasures.

“Let me change my words / Show me where it hurts.”

Thank you for reading. I’m not quite ready to face the new decade, so expect more recaps in the (hopefully not-too-distant) future. Until then, I hope your ears find many wonderful new sounds to enjoy. Just turn it up, for fuck’s sake.

02/02/20

Albums of the Year 2016: 6-2

6

Solange

A Seat at the Table

Solange Knowles worked on A Seat at the Table in fits and starts through the eight years preceding its completion, and consequently, there’s a lot to unpack in the finished product. “I’ve got a lot to be mad about,” she makes clear early on, and the tensions and injustices she has felt and witnessed as a black woman propel the entire album. And yet, her anger is channelled into a search for redemption rather than aggressive diatribes: a calm flipside to her sister’s Lemonade, and a moving celebration of black lives and culture that argues for belonging above all else. A Seat at the Table is a fitting title for a record that sounds so inviting: it welcomes its audience to the discussion, its anecdotes and manifestos detailed with grace and patience.

‘Don’t Touch My Hair’ is the kind of protest song that resembles an open palm rather than a clenched fist, its force radiating without the need for dramatics. The same goes for its peers: ‘Cranes in the Sky’ and ‘F.U.B.U.’ firmly push against the bigotry and hypocrisy Solange and so many others are victims to, while remaining admirably open-hearted and generous in spirit. The sound is absolutely wonderful: laced with tasteful touches of Motown and soft funk, A Seat at the Table is heaped with earworms that flutter and snap alongside these celebrations of the self. Solange pitches her tone with fine precision, balancing her steely proclamations with joyous forays into liberating movement – not least on the effervescent ‘Junie’. There’s a lot to be proud about, too: when her mother venerates “the beauty of being black” during one interlude, her plainspoken honesty gets to the warmth at the core of her daughter’s album.

“I hope my son will bang this song so loud / That he almost makes his walls fall down.”

5

Angel Olsen

My Woman

For several years, Angel Olsen’s talent has been in bloom for all to hear, but My Woman is undoubtedly a significant leap forward. No longer the preserve of alt-rock magpies, she has delivered the vigorous pop record that her music previously hinted towards, but seemed to shy away from. She hasn’t abandoned her signatures in compromise, but rather has embellished and fortified them further: the emotional charge is ramped up rather than watered down, and her zeal fills every note, whether her voice is trembling with vulnerability or raw with intensity. Olsen shows more of herself than ever before as both singer and songwriter: whether she’s howling through ‘Shut Up Kiss Me’ or crooning dreamily as she does in the blissful ‘Those Were the Days’, her presence is generously multifaceted.

On an album that merges her folk and grunge trademarks with soulful deliveries and country pep, Olsen’s nous is apparent through the smoothness of the whole. Intentionally sequenced as an album of two halves, My Woman fits together perfectly, the winding jams of the latter side sounding like the natural comedown after the emotional expenditure of the album’s opening salvo. Her techniques as a songwriter are consistent, but she employs them to admirably inventive effect: where the guitar crescendos on ‘Not Gonna Kill You’ forcibly burst out of the song’s fabric, on the spectacular ‘Sister’, the build is akin to seeing fireworks launched in slow-motion: a revelatory moment of wide-eyed wonder that suits Olsen’s own ascension.

“All my life I thought I’d change.”

4

Frank Ocean

Blonde

Channel Orange was far from simple in its constitution, but Blonde is thick with content to such a degree that a full analysis could easily fill a book. There is so much to be derived from its density that it invites patience and investment, coaxing its listeners into blurry, headier places than Frank Ocean’s previous full-lengths. Even if this less straightforward approach makes for a less gratifying listen than the slicker R&B of old, Ocean’s supreme knack for melody keeps Blonde welcoming. ‘Pink + White’, ‘Godspeed’, ‘Self Control’, ‘White Ferrari’: these tracks aren’t always forthright in their hooks, but the care of construction has yielded handsome results that make repeat plays appealing. ‘Solo’ is as rich in meaning as any other cut, but Ocean’s grasp and control of melody and flow elevate the song into a heavenly experience. Even based around minimal tools, ‘Nights’ sounds like a full feast of ideas; an impressive transformation from an anthemic montage of “everyday shit” to a coda of lounge soul, via a sequence of videogame guitar licks.

Blonde presents an opus of life’s makeup through fast years and rough hours. There are narcoleptic hazes (“skipping showers and switching socks / Sleeping good and long”), sudden jitters and outbursts (as nailed by André 3000), stark poetry (“weed crumbles into glitter”) and eloquently-expressed pangs of very modern fear and exhaustion. Ocean acknowledges that he is expected to be a spokesman, but Blonde connects with its broad span of followers by withdrawing into the intensely personal, as in Ocean’s reference to Trayvon Martin. It’s a tiny glimpse at an individual reaction: a haunting gut-punch rather than a polemic.

So often on Blonde, Ocean works magic by hitching deeply complex thoughts to the most mellifluous tunes. His formidable hit-rate would make such accomplishments seem effortless, were it not for the four-year gestation that alludes to the hard graft at this music’s core. This album presents a challenge to Ocean’s peers and listeners alike to match the ambition of his own creativity: a demand that we all raise our game to suit works of this intricacy and power.

“Want to see nirvana but don’t want to die yet.”

3

Car Seat Headrest

Teens of Denial

Whoever you are, if you’re in your twenties – or at the very least, can recall those hard knots of bewilderment and confusion that pierced (and possibly defined) your twenties – then you absolutely need this album. It’s essential. Coming across as a short story collection written with wit and candour, it’s a painfully acute opus set to subtly inventive lo-fi thrills. Will Toledo is no guitar hero, but his second major label album with Car Seat Headrest is thoroughly inspiring. The basic struts of garage rock are present and correct, but they’re dismantled and reassembled with dynamism belying the slacker-band languor Car Seat Headrest are audibly in thrall to. In seventy minutes, not a single hook fails to land.

But it’s Toledo who takes precedence, surrendering feelings towards himself from the very start: “if I was split in two, I would just take my fists / So I could beat up the rest of me”. From this sunny opening, Toledo eloquently stumbles from one ill-fated scenario to another: sobbing after a shakedown with some cops, screaming through an onset of social anxiety during a gig, trying not to piss his pants during a disappointing drug trip. Teens of Denial is brimful of honesty, hilarity, bewilderment and pathos, bound up in these unfortunate anecdotes that are joyous to hear. Toledo may shrug his way through some of these commentaries, but the lion’s share of them contain genuinely profound observations that stick as fast as the riffery. More ambitious and balanced than 2015’s Teens of Style, Teens of Denial lives up to its delightful song titles and then some. “You haven’t tried hard enough to like it”? It’s impossible to adore this album enough.

“Good people give good advice / Get a job, eat an apple, it’ll work itself out.”

2

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds

Skeleton Tree

Nick Cave’s sixteenth studio album with the Bad Seeds is an unequivocal masterpiece. It’s a wrenchingly sad, haunting, and courageous work from a veteran who revealed a whole new depth of personal and artistic mettle in its creation. Questions regarding what aspects of Skeleton Tree were completed before and after Arthur Cave’s death are hard to dispel, but ultimately, they are rendered irrelevant by a work throughout which the weight of grief, pain and loss is articulated with devastating potency.

On these eight songs, Cave peers into the inky blackness of his imagination, sifting through lurid memories and conjuring surrealist imagery of slow-moving dread. The stalwart Bad Seeds match the desolate subject matter with brooding and eerie soundscapes, on which conventional choruses are few and far between. These songs unspool in oppressive clouds of rumbling distortion and disquieting flickers of noise. ‘Rings of Saturn’ hints towards gorgeousness but consistently retreats, the singer “too tongue-tied to drink it up and swallow back the pain”. The trembles in his voice contribute to the effect of the whole: the stony tone he adopts suggests his deeper anguish is shelled away, but there are times when this protective layer cracks and the monstrous emotional flood begins to pour out. The album’s final stretch is equally agonising and delicate. ‘I Need You’ is almost impossible to stomach as Cave’s relentless refrains become choked with yearning: his wail of “I will miss you when you’re gone” must have been unbearable to witness in the studio. Yet ‘Distant Sky’ and the title track combine to form a touchingly human coda to the sorrows that came before: pleas to let go of the suffering while nurturing the love that we are able to carry further.

In many of these songs, Cave calls out beseechingly into the abyss, and receives no answer. By the album’s end, he hasn’t found peace, but has steadied himself enough to reach a resolution of sorts, albeit a fragile, irrevocably altered one. Skeleton Tree may be forever haunted by its shatteringly tragic context, but ultimately, the music herein is of such power that it is magisterial in of itself. It’s an album I won’t forget: its abstract articulations of pain and grief beyond imagining are profoundly disturbing, but that same despair bears forth a terribly unique beauty.

“You believe in God / But you get no special dispensation for this belief now.”

09/01/16