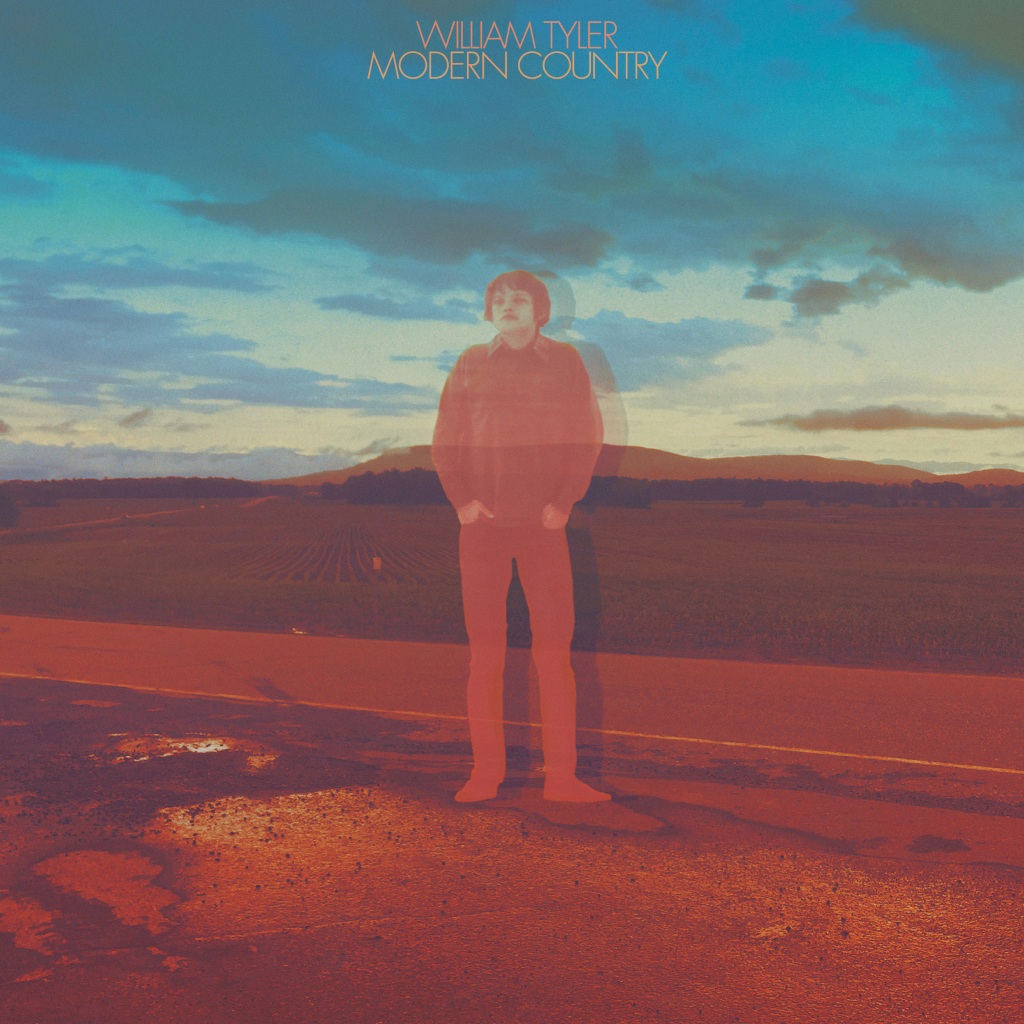

25 More: Modern Country

34/50

William Tyler

Modern Country (Merge, 2016)

“The cultural geography of this vanishing America is what I sense as a slow fade on these long road trips. It still lives, even as the highways and high-rises push it to the fringes of the countryside, and the static of the airwaves. Modern Country is a love letter to what we are losing in America – to what we have already lost.”

William Tyler declared the above in a promotional trailer for his third solo album Modern Country, released on Merge in June 2016. Produced by Brad Cook and recorded with a roster of abundantly talented musicians, it’s the most sonically lush release in a discography that sparkles on all sides. Consistently active since his teenage years – in outfits including Lambchop and Silver Jews – Tyler started releasing albums under his own name in 2010, with that year’s Behold the Spirit and 2013’s Impossible Truth running new power through the circuits of instrumental guitar music.

Tyler is an exceptional guitarist. Watch any footage of him performing, and what is perhaps most striking is the total lack of grandeur in his playing: his studied focus and dexterity are compelling enough to hold close attention. Growing up with musician parents in Nashville, Tennessee in the latter decades of the 20th Century gave Tyler a great nous for the culture and history of guitar music. His reverence for the diverse languages of the instrument is apparent in everything he has released so far, nodding to established classics while nudging the conversation forwards, adapting conventions of the past to complement the milieu of the present.

At their core, his are songs of disarming clarity: pieces such as 2019’s ‘Not in Our Stars’ are wide-open and rich, his deliberate mastery of the fretboard couched in the familiar tones of country music, polished to a modern gleam without losing its rustic warmth. His albums’ wordlessness contributes to their near-timeless quality, unhitched from the temporal and emotional limitations of language. Modern Country retains the intimacy of his earlier works (at many moments, it sounds like a private performance for the listener), but with the addition of a full band of collaborators, it gains a new expansiveness, both sonic and cerebral. This emphasis on spaciousness – and the visual connotations thereof – is key to Modern Country.

When touring the US in the first half of the 2010s, Tyler read The Unwinding by George Packer; a history of American decline in which the author “tells the human story of America’s vertiginous collapse”. Packer took on-the-ground experiences of Rust Belt factory workers, sustainability evangelists, political careerists and Silicon Valley billionaires and wove them into a detailed and foreboding account of the United States’ gradual (but ruthless) shift from industrial to technological capital. In the book’s prologue, Packer posits that “if you were born around 1960 or afterward, you have spent your adult life in the vertigo of that unwinding. You watched structures that had been in place before your birth collapse like pillars of salt across the vast visible landscape – the farms of the Carolina Piedmont, the factories of the Mahoning Valley, Florida subdivisions, California schools [… and] the void was filled by the default force in American life, organised money”.

While Tyler was reading The Unwinding, the tour carried him along backroads through small, now-interstitial American towns, where the unravelling of social welfare and dwindling visitor appeal had cast a gaunt ghostliness over these settings. In an excellent Tiny Mix Tapes interview, Tyler commented that “when you’re travelling, the way I do, touring through the country, you see the fabric of America change in slow fades rather than jarring transitions, because you’re not flying from one city to the other, you’re driving the length”. This meandering and occasionally mournful progression across the land gave Tyler ample time to reflect on the widespread conversion from one set of values to another, and all those left behind in the wake of this glacial transformation: people, places, ways of being. To return one more time to Packer: “An old city can lose its industrial foundation and two-thirds of its people, while all its mainstays – churches, government, businesses, charities, unions – fall like building flats in a strong wind, hardly making a sound.”

On the Bandcamp page for Modern Country, the album credits are suffixed with a line from Frank Stanford’s 1977 epic poem The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You: “all of this is magic against death”. It’s a fitting epigram for an album born from Tyler’s own curiosity about the lives and livelihoods of Americans who found themselves adrift as the foundations on which their lives had been built steadily eroded. The decline of steel and coal industries and the wider shift towards advanced manufacturing and technological innovation shifted the centres of existence towards other geographic sites, the neglect of the Rust Belt countered by population booms in the Sun Belt region. Those who remained behind, doggedly striving to continue along the same channels, or attempting to adapt without uprooting their families, were left living in the “slow fade” of inevitable change. This does not automatically make them martyrs or paragons, their decisions not necessarily founded in nobility or wisdom or righteousness. But many did – and do – continue to exist in these towns and cities: living testaments to very human responses in the face of unfathomable transformations in a country’s culture. To continually strive for certainty in the face of monolithic upheaval is surely at the core of “magic against death”. (Incidentally, Stanford himself committed suicide, one month before his 30th birthday.)

These reflections hum along underneath the surface of Modern Country. The album’s song titles and the occasional sweep of its music gesture towards specific and abstract reference points respectively, but the instrumental form largely gives listeners the freedom to explore and infer as they please. The album’s pleasures are far from didactic; it is a textured ambient record every bit as effective as it is one of applied, wistful Americana. Some of its songs allude to specific historical episodes, such as ‘Kingdom of Jones’ – a Mississippi county in which a civilian rebellion was led against the Confederacy during the Civil War. It is in such moments that Tyler’s talk of a “love letter to what we are losing in America” is made particularly clear, thrown into sharper relief by the attitudes highlighted across the United States in the year of Modern Country’s release. In this sense, Modern Country is a highway of Tyler’s own making. Each listener can pay attention to the scenery as much or as little as they choose to. Along the way, there are signposts to different areas to explore, should you like to travel those roads, but Tyler leaves those choices to you, fine-tuning the medium rather than the message.

Which is perfect, as the seven songs themselves are stunningly beautiful. Modern Country is the work of virtuoso musicians, all working in service of the whole, without recourse to spotlighted moments of individual heroism. The performances here are signposts in their own right: from Modern Country I branched off to listen to Luke Schneider’s album Altar of Harmony, and various projects featuring Phil Cook (Megafaun, DeYarmond Edison, Gayngs). Delving deeper into the credits, it’s clear that Modern Country is the work of people who have poured their lives into music, dedicated to exploring and perfecting sounds and textures in ever-evolving dialogues with others. The convergence of these particular performers is glorious on Modern Country; an album so rich in beauty and atmosphere that, in its finest moments, it takes flight.

Modern Country is bookended by its two longest – and to my ears, most beautiful – songs. ‘Highway Anxiety’ centres on Tyler’s cushioned electric guitar unribboning across nine gorgeous minutes, gradually joined by swirling clouds of pedal steel, clangourous kosmiche piano, and the shuffling snares of Wilco’s Glenn Kotche. Named for the panic attacks Tyler reportedly battled during some of the longer stints of his previous tours, the track is a balm of faintly spiritual qualities, capturing the grace and sublimity of a sunrise cresting a distant mountain range. Its equal on the album is the triumphant closer ‘The Great Unwind’, whose surging, shredding guitars disperse into birdsong and fresh air, before a gentle, dusky jam settles in as a coda for all that came before. The track fades slowly, its melodies unfurling with luxurious bittersweetness: a landscape fading in the rear-view mirror. It’s a song that approximates catching sight of a stunning panorama, or being on a journey safe in the close company of a soul partner: a moment you hope to live inside forever.

Of course, no-one can. No matter its length, whether it lasts for a second or for several decades, a moment passes and is lost. All that remains are memories, and whatever tributes have been articulated that will preserve a quality of those memories, themselves finite. Without words, Modern Country works with this understanding, memorialising the once-prosperous places and people that Tyler encountered when driving the length of America. He doesn’t need to preach his case with words: Modern Country conveys more than enough with its rich, warmly familiar palette. This is the sound of musicians embracing the “classic” tools of Americana, and finding fresh strength within. That Frank Stanford epigram couldn’t be more fitting: much like Jake Xerxes Fussell (another favourite of mine), on this album, William Tyler invokes a magic against the death that is forgetting, kindling small but resilient fires against the encroaching darkness of new eras that leave so much behind.

11/07/21

Support: williamtyler.bandcamp.com

25 More: Suck it and See

33/50

Arctic Monkeys

Suck it and See (Domino, 2011)

When May gave way to June in the summer of 2011, I was in New York. I was there for a long weekend break with my family, occupied by the standard activities: we saw the sights, caught a Broadway show, went nightwalking just for the joy of it, and generally revelled in the atmosphere. And every evening I’d pay for half an hour’s use of the guest computer in the hotel lobby, just to see if any new reviews or promo for the upcoming Arctic Monkeys album had appeared online. On our final night of the trip, I saw that the NME had reviewed Suck it and See, with a score of 9/10. I don’t remember ever being so excited by the sight of a rating in the music press.

I was 18 years old at the time, and deep in that deliciously nerdy headspace of young fandom, fully keyed into the thrill that comes with anticipating an imminent release from a favourite group. I’d gone so far as to set aside the launch date for immersing myself in the final product: a luxurious time to peruse the album packaging, pore over the lyrics, and to finally and repeatedly hear the songs themselves in full, beyond what had already been unveiled in singles and sneak peeks. I still feel measures of that magic in awaiting new music today, but in those years – my late teens, before I had Spotify, when I was buying CDs multiple times a week – the pleasure was even greater, undulled by the modern saturations of instantaneous access and my broader awareness of available releases. For weeks after I bought Suck it and See, I stuck to it like glue.

The summer of 2011 holds a special place in my memory, which is heavily rose-tinted after the intervening decade, the doldrums of the period bleached away by recollections of sunshine, freedom and excitement. At the time, I considered it to be the last summer of my “childhood”: I was at the tail-end of a year out of full-time education, and in the final weeks before I left my hometown for university. My time was built around mostly simple pleasures: consuming books and movies and music, cycling to and from my café job six mornings a week, learning to drive, messing around with my band. Baking-hot afternoons were spent in my friend Matt’s garage, noisily and sloppily bashing out our small repertoire of original songs, and some basic but fun cover choices. (Sadly, we never did record our envisaged EP. Godzilla Wins, Hands Down still only exists in our heads, and in fragments of recordings captured on Matt’s laptop. Still, never say never.)

It was a singular time in my life, and my obsession with Suck it and See rested at the centre of it all, its songs indelibly bonded to the events and emotions of those months, and the experiences that were waiting just on the horizon. I’ve written numerous pieces about the evolution of Arctic Monkeys, and why my ardour goes beyond casual enjoyment into a grateful kind of adoration. They are the band I grew up with, and I love them dearly not because every album is stellar (though that could certainly be argued), but because the members’ personalities shine through their recordings. Each album has felt like an organic and creative glimpse into the lives of the members at each juncture, from snarky teenagers getting nightlife kicks in Sheffield to global superstars building their own strange worlds to populate, complete with rooftop taquerias and Steinway pianos.

Suck it and See followed 2009’s Humbug, the band’s gear-shifting third album which ultimately jettisoned a sizeable portion of their fan base, thanks to its stoner-rock crunch partially indebted to co-producer Joshua Homme. Following that album’s artistic line-in-the-sand – a decisive decision to follow their own whims rather than retread the same ground as before – Suck it and See conveys the unburdened sense of freedom that ensued thereafter. Having proven their willingness to push beyond the sound of their early years, and with the hype bubble significantly deflated, the Arctic Monkeys had successfully reduced the weight of expectation for album number four, and the result is their loosest and most charmingly direct collection to date.

Humbug and Suck it and See are not necessarily Great Albums in the objective sense: their cultural influence is limited compared to any of the band’s other albums, and as listening experiences, they’re less cohesive than their peers in the Monkeys’ catalogue. But they are the kind of albums that enrich artist discographies by dint of character and stylistic variation. Both albums capture the four bandmates loosening up and allowing themselves to wander into fresh pastures. Stylistically, Suck it and See is a (slightly bizarrely sequenced) mixture of summery guitar pop and muscular, riff-based workouts, dominated by the former but originally advertised by the latter. The first two tunes to leak from the album were by some distance the most ridiculous things the band had ever put to tape: ‘Brick by Brick’ and ‘Don’t Sit Down ’Cause I’ve Moved Your Chair’ sound more like practical jokes being played on their listeners, giving no indication of the sweet, 60s-flavoured jangle that fills so much of the album proper. After three albums of witty locquaciosuness, many were appalled by the absurdity of these teaser tracks – some still are.

For what it’s worth, I will happily crow until the end of time how much I fucking love ‘Brick by Brick’. It’s the big, dumb first release which – combined with the double entendre of the album title, the Black Sabbath-cribbing band logo, the beardy snaps of the band in sun-bleached LA convertibles – wrongfooted everyone into believing Alex Turner and co. had transformed into hubristic hard-rock dunderheads. Based around a mind-emptyingly simple riff and a cheerfully brisk vocal performance from drummer Matt Helders, ‘Brick by Brick’ sounds like a gimmick – another punchline from the same band who once turned up to the Brit Awards dressed as the main characters from The Wizard of Oz. But by my reckoning, ‘Brick by Brick’ is essential to the enduring charm of Suck it and See. Beyond the overt humour of the track is a heartening sense of identity; the sound of four twentysomething friends suspicious of the allure of fame, and content to counter any remaining hype with a few chunky, gratifying power chords. Helders hollers with a gusto that’s underpinned by a paradoxical sense of silliness and earnestness. “I wanna steal your soul!” he bellows in the second verse, before thrice repeating the none-more-hubristic refrain “I wanna rock and roll!” The low-register rumble of bassist Nick O’Malley follows with the droll suffix “brick by brick”. It’s a song that’s barely trying to make sense.

It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t need to matter, and it never needed to matter. Not every work needs to be weighed on the scales of greatness, held up to dizzying standards and then reviewed and ranked accordingly. The members of Arctic Monkeys were in their mid-20s when they wrote and recorded these songs. ‘Brick by Brick’ is the clearest manifestation of the playfulness that the group were keen to hold onto for as long as possible in the face of stardom’s distortion. The same good-humoured spirit rings throughout Suck it and See, and not only in Turner’s wry jokes and turns of phrase (“her steady hands may well have done the Devil’s pedicure”). ‘All My Own Stunts’ is bookended by the band goofing off in the studio, closing with a snippet of a novelty song the band penned for their own amusement, titled ‘I’m From High Green’, which took aim at the group’s evolution from Yorkshire upstarts to international rock stars. “I lost my accent / I live the dream / But I still like my ale / Because I’m from High Green.”

This lightness of touch pervades the album, on the poppy and crunchy numbers alike. One of my favourite cuts is the heroic ‘Black Treacle’, whose reverberant chords are topped with one of Turner’s most boyishly sprightly vocal performances. There’s a sweetness to his voice and delivery as he begins the song: “Lately I’ve been seeing things / Belly-button piercings / In the sky at night / When we’re side by side”. Even these softer moments are beefed up by the production of James Ford, who foregrounded the Helders / O’Malley rhythm section; the bass-forward low-end giving body to the lovestruck sparkle of Turner’s vocals. For many of these songs, Turner is driven to distraction by infatuation: by turns, the singer is horny (‘She’s Thunderstorms’), pining (‘Suck it and See’), agitated (‘The Hellcat Spangled Shalalala’) and generally at a loss (‘Reckless Serenade’). Twinned with Turner’s beguiling solo EP (the soundtrack for Richard Ayoade’s Submarine), the songwriter was at his most hopelessly romantic in 2011, his keen eye for telling details translating beautifully to major-key love songs. Suck it and See is studded with exquisite passages: “the type of kisses where teeth collide”, “she looks as if she’s blowing a kiss at me / and suddenly the sky is a scissor”, “I tried last night to pack away a laugh / like a key under the mat”. Turner still throws a few sarky barbs and tongue-trippers into the pot, but for the most part he sounds his age: earnest, self-effacing and endearingly clumsy as his feelings for another bloom.

The clincher for Suck it and See is its glorious sun-kissed finish. Brimming with lush melodies and shifting between romantic yearning and a tantalising sense of yawning possibility, the final stretch of the album contains the loveliest crop of songs the Monkeys have yet recorded. ‘That’s Where You’re Wrong’ is a wonderful closer, and as a complete track, it’s the wistful highlight of the record. But it’s the title song that contains my favourite moment on any Arctic Monkeys album. The final seventy seconds are so ecstatically dreamy: “sit next to me before I go” is one of the simplest, prettiest refrains in Turner’s songbook. Helders’ backing harmonies are golden-hued and gorgeous, especially when he jumps an octave in the final moments. Having elsewhere pondered stormy intimacy and laughter like a “stun-gun lullaby”, Turner sounds like a shy teenager as he likens his crush to a fizzy drink, hoping to share a moment or two before the world moves on. I can never listen to it just once on a play-through.

I was so attached to Suck it and See that summer ten years ago, and its songs steadily informed – and were informed by – events of the subsequent months. My band shuffled through further afternoons attempting to learn ‘She’s Thunderstorms’ and ‘Reckless Serenade’, and a few of us went to see Arctic Monkeys perform at the O2 Arena that autumn. In October, I set off for university, the drive soundtracked by Suck it and See, and those first weeks were spent bonding over beloved cultural touchstones. A particularly significant friendship was sparked by the fervent love that the two of us shared for Arctic Monkeys: two kids from opposite ends of England, each fresh from a summer spent living inside the twelve songs of this album. I can’t express how important said friendship has proven to be over the past decade. It’s one for which I’m immeasurably grateful, and our bond over this band has continued to feel foundational. When the two of us saw the group’s Royal Albert Hall performance in 2018, it seemed like a communal moment of ecstatic reverence that we both felt incredibly fortunate to enjoy together.

This all came later. Ten years ago, I was a spotty, shaggy-haired teenager on holiday with my parents and sister, checking a hotel computer in the hopes of absorbing as much information as possible about a quartet of twentysomething mates who had found success making music, and were set on having fun doing so. I’m 28 now, and there are great swathes of time in which I feel less complete as a person than I used to be. I’m still young, but the direction of my life feels less certain these days. There are aspects of my history and personality that I’m not proud of – some will be worked through with time, others are irrevocable. There are repeated periods when sighting a way forward feels like a challenge I’m simply not up to. It’s because of this that I’m especially appreciative of the sources of joy that have remained constant throughout the years, and throughout the various versions of myself. Suck it and See – and all the memories with which I’ve come to associate it – feels very poignant in this regard. My fondness for it only grows with time, and I’ll continue to carry it with me through whatever waits down the road, even if I’m not sure what that will be. As Turner himself put it on ‘That’s Where You’re Wrong’, “there are no handles for you to hold / and no understanding where it goes”.

Make a wish that weighs a tonne.

06/06/21

25 More: The ArchAndroid

31/50

Janelle Monáe

The ArchAndroid (Wondaland, 2010)

A mere summary of The ArchAndroid should be enough to convince anyone of Janelle Monáe’s voracious appetite for creation. One of the most successfully abundant albums of the 2010s, The ArchAndroid is a concept album primarily based in funk, art-rock and contemporary R&B, but which cherry-picks from a full rainbow of genres across its eighteen tracks. There are sweeping orchestral overtures, moody monochrome jazz passages, Big Band horn sections, swinging Motown vocals and muscular beats, to name just a few. Monáe’s cut-glass voice covers ground from crooning soul to rapid-fire tongue-lashing, able to command whatever sonic environment it’s placed in. The immediate pleasures of The ArchAndroid are myriad. But the album’s genesis, production and finer details yield further revelations: the more one learns about it beyond its surface splendour, the more compelling and remarkable it becomes.

While working on The Audition – her first full “demo” album, released in 2003 – Monáe (full name Janelle Monáe Robinson) established a close creative and business partnership with Chuck Lightning and Nate Rocket (aka Charles Joseph II and Nathaniel Irvin III, who together form the enigmatic “Punk Prophet” duo Deep Cotton). Based in Atlanta, the three of them co-founded the Wondaland Arts Society: a studio / record label / arts collective / production company, for which Monáe holds the position of CEO. Working from Wondaland, Monáe recorded her 2007 EP Metropolis: The Chase Suite, which caught the attention of Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs. Impressed by Monáe’s already-prodigious talents, Combs approached her with an offer to join his roster on the Bad Boy label. After some negotiating, Monáe accepted on the condition that she continue operating with the Wondaland Arts Society, and that she and her partners maintain autonomy over the direction, production and promotion of their work. Now with a significantly larger platform from which to launch her output, the combination of Monáe’s sound business acumen and undiluted creative principles gave her and the Wondaland team the freedom to craft her proper debut album with minimal concessions. By the time The ArchAndroid was released in May 2010, Monáe was 24 years old. Take a moment to let that sink in.

Alongside a polite commercial reception, The ArchAndroid was widely adored by the music press, with the album and its lead single ‘Tightrope’ appearing in many (and topping a few) end-of-year lists. The scale of The ArchAndroid and the magnetism of its creator-in-chief brought Monáe regular comparisons to musical visionaries, most notably David Bowie, Prince and Stevie Wonder. Comparisons to such artists have been cheapened across decades of overuse, now all-too-often used as a superficial shorthand for any vaguely eccentric performer operating outside of clear genre lines. But in Monáe’s case, these comparisons were completely justified: on The ArchAndroid, she wields the queer charisma and omnivorous hunger of Bowie, channels the kinetic funk of Prince (with whom she would go on to collaborate in future projects), the tight pop confectionary and tight choreography of Michael Jackson, the bombastic savvy of Outkast. Taken together, such namedrops could raise suspicion of a wild flailing for attention, but the results are fluid and tasteful: The ArchAndroid is an assured, competent and charismatic fusion of sounds, styles, and (musical, thematic, aesthetic) influences from art of many stripes.

The album is the second entry in Monáe’s ongoing Metropolis saga, which of course takes its name from Fritz Lang’s dystopian epic. The series – divided into four “suites” (since extended to seven) – began with Metropolis: The Chase Suite, in which Monáe introduced the story of Cindi Mayweather: an android living in the year 2719 who is sentenced to “immediate disassembly” after falling in love with the human Anthony Greendown. Over the course of The Chase Suite, Cindi is pursued and captured by bounty hunters; a narrative which is corroborated (and occasionally contradicted) by the accompanying promotional material. In the standout track ‘Many Moons’, Monáe sings of a dystopian city in which androids have been othered and suppressed: “all we ever wanted to say / was chased, erased and then thrown away”. Comprising the second and third suites of the saga, The ArchAndroid deepens the story’s mythos, with its record sleeve featuring an intriguingly pulpy premise that tells of Monáe’s original existence in the year 2719. In said year, she is abducted by “bodysnatchers”, who duplicate her genetic code and transfer it to an android named Cindi Mayweather. The original Monáe is sent back in time to 2010 by a secret society called the Great Divide, which uses time travel to “disappear” anyone threatening to build a bridge between segregated cultures. In the future, rumours circulate that Mayweather is the messianic ArchAndroid: a figure destined to save the subjugated androids of Metropolis from the tyranny of oppression.

It’s bold stuff, not least when you consider the album had its own short teaser trailer, its videos further developed aspects of the Metropolis storyline, and Monáe allegedly planned to develop a graphic novel companion piece to the album. (There’s some concept art floating around online, though plans for the latter apparently fizzled out.) An album that incorporates this kind of world-building can incite the equally understandable polar responses of excitement or exhaustion. Both are perfectly valid, but when listening to The ArchAndroid, you can buy into the greater narrative as much or as little as you please: it works as a generous additional layer that doesn’t stifle the appeal of all else on display. And like the strongest works of science-fiction, its chief concerns are wholly rooted in the here-and-now, Monáe combining far-flung escapism with contemporary confrontation. In a 2013 interview with Paste, Monáe elaborated further about the android heroes of her work: “When I’m talking about the android, I’m not talking about an avant-garde art concept or a science-fiction fantasy; I’m talking about the ‘other’: women, the negroid, the queer, the untouchable, the marginalised, the oppressed.”

Monáe’s Metropolis saga is bursting with questions of identity and belonging. Interestingly, Monáe’s only non-Metropolis album to date is the one which has gone furthest in establishing her as a champion for self-discovery and sexual, racial, and cultural tolerance. Released in 2018, Dirty Computer’s hook-heavy bangers of social acceptance are the most direct calls for compassion from Monáe’s catalogue thus far: stripped of the conceptual density of her Metropolis work, Dirty Computer is much more overt in its assertion of positive, progressive social messages. But such threads are wound into The ArchAndroid too, exploring as it does the persecution of otherness, and the plight of individuals striving to transcend and escape the mores and regimes that prolong their subjugation. In a sense, Dirty Computer is the bottom-line of The ArchAndroid given explicit form: the choice to build communities rather than succumb to division, and finding the courage to live in love rather than contribute to cycles of fear and hatred. On the showstopper finale of ‘BaBopByeYa’, Monáe/Cindi announces that “this time I shall be unafraid / and violence will not move me […] I see beyond tomorrow / this life of strife and sorrow”.

The double-album format suits The ArchAndroid splendidly, giving a sense of breadth and luxurious detail to proceedings. More than fifty musicians contributed to the record, incorporating pan-cultural sounds and styles that Monáe and her partners explored while touring with of Montreal. But a diverse instrumental palette alone isn’t a guarantor of success: it is the work of Monáe and her team to compile everything into a fluent whole, which they do with aplomb. The ArchAndroid sounds immaculate. Monáe exudes an effortlessness in her performances (both onstage and on record), but the amount of work that went into this project is apparent at every turn, in the scale and quality of the music, its lyrical content, its visual packaging. Everything fits into place so snugly, the full-bodied production warm and richly detailed: basslines pulse through songs like blood-pumping arteries, itchy-footed guitar licks are mixed at a perfectly cool distance, backing vocals sink and soar and explode in fireworks. Even on a first listen, to hear the opening stretch of The ArchAndroid is like settling into a beloved favourite, such is the easy confidence it inspires.

The first moments of the album suggest a portal being opened: ‘Suite II Overture’ ushers the listener into The ArchAndroid with a lusciously dramatic orchestral arrangement worthy of Rodgers and Hammerstein. It’s the sound of a curtain rising on a stage of cyberpunk sets, a cast of suppressed others in the form of androids, and a tale of romance, freedom-fighters, and time-travel. Any listeners eager to dive deep into Monáe’s mythology can start filling their boots from here. For those who came for the tunes, the sound is engrossing regardless, and when I listen today, I still feel that rare thrill of being eased into a gorgeously assured piece of work. The ArchAndroid is a carousel of styles and spectacles, each one pulled off with charismatic confidence. Suite II is a near-delirious run of ear candy, peaking with the sprinting boom-bap and decadent glam guitar of ‘Cold War’, which is sharpened by Monáe’s wail of “I was made to believe there’s something wrong with me”. The following ‘Tightrope’ is a funk masterclass, swaggering with additional Atlanta pride as Big Boi arrives to drop a fittingly acrobatic verse. The song’s final minute is a glitzy showcase of virtuosic scratching, a call-and-response refrain, and an appearance from “the funkiest horn section in Metropolis”. Things are just as intoxicating beyond the bangers: the interlude ‘Neon Gumbo’ is a mist of backtracked vocals, thunderclouds and guitar scribbles that leads directly into ‘Oh, Maker’, where pastoral folksiness is recast into an impassioned soul ballad by the arrival of a thumping beat and one of Monáe’s loveliest – and most skilfully performed – choruses. An ode to prohibited love, ‘Oh, Maker’ is grapeshot with plainspoken beauty (“I hear the drizzle of the rain / It’s falling from my window”) as Monáe/Cindi navigates the wreckage of a broken society by leaning into the burning yellow of her passion. Sung in her higher register, the line “perhaps what I mean to say / is that it’s amazing that your love was mine” is an indelibly perfect moment on an album brimming with quality.

The pace slows during Suite III, the drama unfolding in a quieter fashion on ‘Neon Valley Street’ and ‘57821’. The final combo of ‘Say You’ll Go’ (which interpolates ‘Clair de Lune’) and the three-part curtain call ‘BaBopByeYa’ gathers the strands of the previous hour and gives all a spotlight send-off. Combining flavours of brooding jazz, Latin ballroom and a final swell of fairytale strings and horns, ‘BaBopByeYa’ is an incredible note to go out on, and is all the more poignant considering it allegedly took shape over the course of several decades. The only odd fit on Suite III is the self-consciously wacky ‘Make the Bus’, penned (and sung) by of Montreal’s Kevin Barnes; the only song here for which Monáe doesn’t have a writing credit. But this slight deviation doesn’t damage the whole; ‘Make the Bus’ still possesses the wild enthusiasm that is The ArchAndroid’s calling card, which is emphasised when Monáe clicks into full beam on the glittering ‘Wondaland’. The spirit and playfulness of the whole enterprise remains ripe, whether manifested in the hook-heavy assault of the opening stretch or the grandeur of the album’s conclusion. The ArchAndroid operates as a magnificent musical adventure, but is an experience fully worth investing in. The more you give to it, the more is given in return.

In a write-up of Random Access Memories, Dorian Lynskey observed that Daft Punk shared Chic’s “aspiration to make luxury products for mass consumption”, noting that both groups present an “effortlessness that can only be achieved by months of painstaking effort. They sweat and strain so you don’t have to”. The same can be said of The ArchAndroid. The graft and dedication behind it is mind-boggling, but the final product is supremely welcome on the ears: outward-thinking, forward-facing pop music to be enjoyed, replayed and pored over with pleasure. To return to those comparisons to Bowie and Prince one more time, I think Monáe lives up to them most of all because she doesn’t seem to consider any given aspect of her work to be of greater or lesser value than another. Her mission isn’t to smuggle social commentary into disposable earworms, nor does she use lazy loftiness to draw attention to her knack for songcraft. She aligns everything into a singular whole: social politics and pulpy sci-fi, instantly gratifying bangers and orchestral flourishes, her time in the spotlight and her integrity as both artist and businesswoman. It’s a tightrope she walks in perfect balance, treating every aspect of her work with the same respect and enthusiasm. The ArchAndroid is a wonderful album, because no matter where you choose to look, thought, care and excitement have been poured into it.

28/03/21

25 More: Alive 2007

30/50

Daft Punk

Alive 2007 (Virgin, 2007)

The announcement of Daft Punk’s retirement on 22nd February was unexpected and saddening, but in truth, not altogether earth-shattering. As unelaborate as it was, the ‘Epilogue’ video shared by the duo (extracted from their 2006 film Electroma) gave a sense of closure to their dissolution: a welcome case of a successful act bowing out on its own terms. So far, there have been no reports or indications of animosity, creative differences, or tragic circumstances behind the decision, which suggests that Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo called it because it was simply the right time to do so. After a half-decade which has seen an upsetting number of artists exit due to death or disharmony, in many ways, the ending we’ve been presented with is a happy one. As minimal as Daft Punk’s announcement was, it has become an all-too-rare experience to see a group concluding its business in a way unmarred by sorrow or distress.

Moreover, as sad as it is to know that Daft Punk won’t be gracing our ears, hearts and minds with further electronic wizardry, their rate of productivity in the latter leg of their career was hardly industrious enough to send shockwaves rolling through the world at the news of their disbandment. Their steady output of 1997 to 2013 had long since settled, with the back half of the 2010s distinguished by less bombastic ventures for the group: a pop-up shop of career memorabilia and artwork, an exhibition at the Philharmonie de Paris, a few features and performances, and rumours of possible soundtracks and collaborations. In hindsight, some of these projects – specifically the art exhibition and pop-up shop – seem indicative of a final victory-lap: a public stock-taking of achievements across their career, their main mission(s) accomplished. Looking back at Random Access Memories – a grandiose whistle-stop tour of the duo’s most beloved influences and touchstones – it nicely operates as a fitting send-off for the group’s recorded output, and a love letter to the act of musical creation itself. There’s a bittersweet sense that, sad as it is to say goodbye, Daft Punk left no business unfinished.

That said, it’d be churlish to move on from this news without celebrating what made Daft Punk so special for so many listeners and fellow artists. In crossing from pioneers of French house to innovators of electronic pop, Bangalter and de Homem-Christo maintained a crowdpleasing savvy in their pursuit of dazzling sounds. The harshest criticisms consistently levelled at Daft Punk are usually rooted in the overexposure of their biggest singles: ‘Get Lucky’ became particularly divisive in its ubiquity through the summer of 2013, and there are some people who still groan at the sound of ‘One More Time’ dropping at a New Year party or squealing from a shitty pair of headphones from a fellow bus passenger. Overexposure will dull the shine of even the most sparkling tune, but while some of Daft Punk’s recordings have become inescapably familiar, the duo wore their popularity with such charm. It never sounded like Daft Punk were courting the attention of their listeners; more that they knew exactly where to encourage them to look, their own immaculate productions and mind-boggling samples giving their fans portals into a wealth of styles and artists to explore. And they remained catchy as hell, the graft of their work hidden beneath the most effortless of appearances. We will never know another act to light up hearts and dancefloors in quite the same way.

The various responses fans have had to every leg of their history speaks to Daft Punk’s range, and the skill with which they navigated these different paths. There is no definitive Daft Punk album, because to fixate on one would be to miss the broader picture. Upon seeing the news on 22nd February, I knew I wanted to write something in tribute to them, and the first album I reached for was Discovery, which was my original gateway into their music. Discovery was everywhere during my time at college – or rather, I was attuned to notice its every incidental appearance, from which I extrapolated that Discovery was the album to listen to. (Even though in truth, Daft Punk were being played and talked about with no greater frequency than other groups. It was 2009, not 2001.) For a time in my life, its songs were chirruping away at the edges of all sorts of experiences. At a sleepover, a casual viewing of Interstella 5555 blew me away, its eye-popping visuals and incorporation of the album into a film narrative completely winning over my imagination. On a course trip to Greece, my roommates set ‘Aerodynamic’ as our morning alarm, the peals of bells (and if we weren’t quick enough, scribbles of compressed guitar) invading our dreams all over the country. I spent hours listening to ‘Digital Love’ and trying to transcribe its ecstatic guitar solo. I dropped ‘Face to Face’ onto CD mixes for long drives, thinking I was cool for choosing something that wasn’t an “obvious” hit. I fried one copy of the album because I kept endlessly skipping back to replay ‘High Life’. It made me question my tastes after years of stubborn guitar-centric exclusionism. Friendships were founded and strengthened by shared love of Discovery, and it has always been close to my heart. It remains an elixir, a treasure chest of addictive songs beamed down from Heaven.

But Discovery alone doesn’t capture the full brilliance of its creators. It doesn’t speak of the meaty house-funk workouts of Homework, the staccato and stripped-back mantras of Human After All, the monster jams of Alive 1997 or the widescreen dazzle of Random Access Memories. Discovery’s sugar-crash pop is just one stage of Daft Punk’s metamorphosis, and in truth, no one album reflects their full mellifluousness. Playlists and mixtapes have done (and still do) that particular job better than any of their studio albums, but in the words of Lester Freamon, “all the pieces matter”. There isn’t a “best” Daft Punk album. Each of their releases holds a specific and crucial place in their discography: to rank Homework against Random Access Memories would be nothing but reductive – a good way to sap the joy out of each.

However, if there is one official release that comes closest to giving us a sweeping commemoration of Daft Punk’s brilliance, it’s Alive 2007. It shouldn’t be placed on a pedestal over its peers, but following the news of their retirement, Alive 2007 is the most exhilarating collection with which to celebrate their life and work, capturing as it does so much of what made Daft Punk so special in the first half of their career. While their post-2007 conquests shouldn’t be forgotten (Random Access Memories and the Tron: Legacy soundtrack are both tremendous), Alive 2007 distils much of Daft Punk’s magnificence into a single 90-minute joyride, blending and expanding and renewing all that came before into something utterly dazzling. Unlike its raw and careening (but also excellent) 1997 predecessor, Alive 2007 is precisely put together, but as far from staid as it’s possible to be. Songs from all corners of their catalogue up until that point are spread over one another, overlapping in a seamlessly flowing whole as iconic moments are teased, introduced, whisked away and reprised at unpredictable moments. To listen from start to finish without consulting the tracklist is one of the greatest and giddiest listening pleasures available.

It’s generally agreed that their Alive 2006/2007 tour was one of the most remarkable live experiences of the decade, as creatively and visually spectacular as it was technically accomplished. Running just shy of fifty shows worldwide, with an alleged “fifteen tonnes” of equipment in tow, performed to a total of over half-a-million attendees, the show successfully alchemised the first half of their career into night after night of ecstasy. Alive 2007 captures that year’s show at the Palais omnisports de Paris-Bercy on 14th June, and while it doesn’t synthesise the immediate thrill of being physically present, like Talking Heads’ Stop Making Sense, it encapsulates and immortalises the vitality of the show and its creators at the peak of their abilities. There’s a wonderful inclusivity to live recordings of this care and quality, defying financial, geographical, physical and temporal limitations to bring a spectacular experience to all. The tour from which Alive 2007 was taken needed this kind of distribution, not because it deserves to find the biggest audience possible, but vice versa: everybody deserves to experience it.

Even if you weren’t present, the album sounds so irresistibly good that it immerses the listener completely in its bubble. Alive 2007 is wide-eyed and animated, the sound of a friend throwing an arm around you and charging into the centre of a crowd of similarly adrenalized fans. The presence and prominence of the crowd in the mix is crucial to the experience: they don’t miss a beat, echoing and amplifying the wild joy of hearing these songs meld together. Unlike the patronising sting of canned laughter, these cheers allow us to share in the communal euphoria of the show’s most gleeful moments, like the sound of ‘Television Rules the Nation’ flipping into ‘Crescendolls’, or the ‘Around the World / Harder Better Faster Stronger’ mashup rising to a deafening crescendo. To simply list them all would be to spoil the magic, but the effect is sustained for the full runtime, right through to the magnificent encore. When Romanthony’s refrain for ‘One More Time’ is layered over the top of a merging of ‘Together’ and ‘Music Sounds Better With You’ from two of Bangalter’s other projects, it’s like seeing a huge, disco-ball-sized cherry being placed on top of a teetering, towering cake.

Perhaps the greatest revelation of Alive 2007 is how it breathes new life into the cuts from Human After All. Hailed as a disappointment on its 2005 release, in a life capacity, even the dampest of squibs from that album are transformed and recontextualised among their peers. The mash-ups are so perfectly realised that you wonder if the studio release of Human After All was one gigantic sucker-punch: a brilliantly executed long-game gambit that paid dividends during the subsequent tour. All refrains from Human After All absolutely slap on Alive 2007, and the former’s highlights (‘Robot Rock’, ‘Technologic’) sound immediately iconic, and are welcomed as such by the rapturous crowd.

Being deprived of live shows over the last twelve months has been a great loss for musicians and fans alike: a dependable source of delight and kinship with strangers dashed, and possibly irrevocably altered. Live streams have been a commendable palliative, but the absence of a crowd in these performances is a sad reminder of our distance from normality. Live albums as good as Alive 2007 have been a major source of solace during the past twelve months, allowing us to tap into that sense of community once again, even if we weren’t physically present at the show we’re hearing. There are listeners drawn to live shows to hear their favourite songs expertly reproduced: a testament to the skill and dexterity of the artists in a live capacity. But the thrill of surprise and spontaneity is a much greater draw. We flock to gigs with certain expectations, but we hope to be surprised, thrilled and dazzled by the magic of each unique performance. Mash-ups, covers, onstage antics, the unpredictability of the night, the crowd, the thousands of incidental details and possibilities that charge the atmosphere. This year, albums like Alive 2007 have gone some way to fill the void left by the absence of concerts: precious glimpses into the experiences we miss dearly, and hope will be within reach again one day soon. For its part, Alive 2007 is one of the most immediately enjoyable choices available. It’s an ever-accessible opportunity to join the crowd and revel in the mastery of an iconic pairing as they collage together their highest of high points.

All of Daft Punk’s releases deserve to be listened to, re-listened to, and cherished for years to come. Each of them holds its own unique space in their catalogue, and the story wouldn’t be complete if any one of them was removed. But the closest thing to an official album that captures so much of what made Daft Punk so brilliant in their ascension is Alive 2007: a reworking of all that came before, presented in glittering splendour. It’s an evergreen party album, a tonic for the blues, and a jewel of the live album form. Bangalter and de Homem-Christo may have retired as a pair, but by releasing Alive 2007 they gifted the world a party that can always be returned to, one where their miraculous dexterity is at its most deliriously fun. Because more than anything, Daft Punk were fun. So, so much fun. Theirs was a one-of-a-kind union that dismantled the fences separating multiple genres and fandoms, gifting us music that simultaneously meant so much and so little, so wonderfully.

07/03/21

25 More: Emperor Tomato Ketchup

29/50

Stereolab

Emperor Tomato Ketchup (Duophonic, 1996)

I’ve always associated ‘Metronomic Underground’ with travelling on the Tube. There are a couple of reasons for this, most basic of which is the obvious mirroring of its title with London’s subterranean labyrinth. Just as simply, I was taking the Tube when I first heard the song, wending my way through the tunnels of Kings Cross to get to the Piccadilly line. Memory and nostalgia certainly play a part in my feelings towards the track, but the deeper I’ve gone into Stereolab’s output (their sound, their preoccupations, and the discourse surrounding them), the more parallels I’ve found in ‘Metronomic Underground’ to living and travelling in the urban sprawl. To my ears, it mirrors the regular eddies into chaos and clutter that you find in cities like London, especially as hundreds of individuals pass through the same spaces all at once, in rituals that transform once-gleaming sites of (supposedly) prosperous modernity into unremarkable backgrounds for human congestion. The once-fresh and striking corridors of the Tube network have become grimy and unregarded conduits for the day-to-day ruckus of rush hours.

‘Metronomic Underground’ follows a similar arc from composure to disorder. Over a bed of burbling sound effects, its constituent parts are introduced one by one, deliberately layered to create a whole that gradually drifts out of control, the song becoming so densely-packed that you can feel a kinetic heat rising through the layers. The originally glossy veneer is scratched and marked by buzzing guitars and tart organ tones, the tempo steadily (almost imperceptibly) accelerating, until the song fizzes to a halt at the eight-minute mark. ‘Metronomic Underground’ doesn’t conclude in total frenzy, but it does point towards one in its slide towards dissonance, like watching someone unravel as the atmosphere around them progressively bristles with activity. The dual vocals of Mary Hansen and Lætitia Sadier give the song an oblique quality, the singers delivering surreal and portentous lyrics respectively. While Sadier drifts in and out with gnomic philosophical phrases (“who knows does not speak / who speaks does not know”, “untie the tangles / to be vacuous”), Hansen insistently repeats the phrase “crazy, sturdy, a torpedo”. We’re given no hints as to what to make of all this: the lyric annotation site Genius humorously summarises the song as one which “imagines what it would be like to be a torpedo”. Instead of being granted a key to any deeper understanding, we’re just left to ride with the song, all of its empty spaces filling up as if the listener is being jostled in an increasingly full train car.

Put like that it sounds deeply unpleasant, but ‘Metronomic Underground’ is one of my favourite songs, and there’s such a cheerfulness to it, palpable in the poppiness that shines through its various quirks. The same goes for many of the songs on Emperor Tomato Ketchup: in their sweetness and sourness alike, there’s a spirit of enthusiasm to the arrangements and performances here, with so many ideas tumbling around within. Some results are less appealing than others, but you can hear the members of Stereolab revelling in the joy of creation, of plugging different elements in and seeing what emerges. The album’s peculiarities are not forced hustles for attention, but natural eruptions from a band with voracious musical and topical appetites. “I don’t like things too clean,” founding member Tim Gane explained to the LA Times in 1996: “I like a bit of spillage”. He was referring specifically to the distortion applied to the guitars and vintage synthesisers that are all over Emperor Tomato Ketchup, but the phrase applies just as well to the general approach taken on this album. There’s no easy flow to it: the songs collide messily in the sequencing, the bilingual lyrics are sombre and confrontational, and the album is all over the place stylistically: a blur of conventions pulled from various genres that are sometimes only unified by a particular guitar tone or the self-absorbed blip of a looped sound effect.

Stereolab fit the description of what music journalist Simon Reynolds has called “portal bands”: groups whose releases “directed their fans to rich sources of brain-food, a whole universe of inspiration and ideas beyond music”. This notion feels slightly outdated today, given the transparency with which so many artists now broadcast their own tastes and interests, but Reynolds argues that “the taste map” became more exposed from the 1980s onwards, as an increasing number of bands proliferated whose touchstones were an integral point of their appeal: (such as the Smiths, Saint Etienne and Manic Street Preachers). From their first singles onward, Stereolab were never short on accommodating unusual reference points in their work, and Emperor Tomato Ketchup is oozing with them, from the cover art (pulled from a 1964 recording of a Béla Bártok concerto) to the title (Shūji Terayama’s violent satirical film of 1971) to the nuggets of political philosophy embedded in Sadier’s verses. Eager listeners could lose themselves for days theorising over the many threads of this album, joining string between the group’s left-field artistic choices and their terse critiques of western capitalism. (Though Stereolab’s members have distanced themselves from Marxist labels, Sadier’s admiration of Cornelius Castoriadis is no secret.)

In the final minutes of Emperor Tomato Ketchup, Sadier repeats “you and me are shaped by some things / well beyond our acknowledgement”, as if gesturing to the impossibly tangled histories (personal, cultural, societal) that all led to (and fed into) the previous fifty minutes. Plenty of superior writers (and listeners) have gone into great depth poring over Stereolab’s DNA, but to take a general view, the lyrics of Emperor Tomato Ketchup broadly revolve around socioeconomic disparity. Many of the band’s other releases share this preoccupation with varying degrees of subtlety, and across this album, Sadier and Hansen probe at the roots and symptoms of capitalism’s polarity in direct terms. “What’s society built on?” Hansen ponders on ‘Motoroller Scalatron’, and the answers arrive in waves: it’s built on bluff, it’s built on trust, it’s built on words, it’s built on work. In a tone that occasionally slips into a robotic cadence, Sadier jabs at the complicity of a sedated population, sometimes addressing the very consumers listening to Stereolab’s music. She rails against nihilistic apathy on the two-chord thrash of ‘The Noise of Carpet’ (“I hate your state of hopelessness / and that vain articulateness”), and outlines the reversal of society serving its delegated representatives on ‘Tomorrow is Already Here’. In the standout ‘Slow Fast Hazel’, she and Hansen race breathlessly into their upper registers, singing of pivotal moments in the history of humanity: the invention of the wheel, discovery of fire, the origins of the 20th Century superpowers. The singers surmise that “the transition has been operated forever” in repeating cycles of advancement and regression: how can we remove ourselves from evidently broken systems if we continue to fall into the same traps?

Disaffection creeps through many of these observations, but couched in the handsome vocal pairing of Hansen and Sadier (as well as the colourful pep of the songs themselves), they sometimes sound as if drawn from a place of curious detachment, as if the band are surveying their surroundings and remarking “oh, so this is the future we’ve ended up in?” Stereolab certainly align themselves with a left-leaning perspective in their writing, but the group don’t tip over into polemics or sloganeering. Instead, as Reynolds’ “portal” idea posits, Stereolab plant these thoughts for the listener to dwell (and possibly act) on. It’s not propagandist, but Emperor Tomato Ketchup does invite and encourage its listeners towards further reading and scrutiny of the systems that govern them, in attempts to pierce the “cynical distance” of apathy in the face of entrenched social systems.

However each subjective listener responds to the lyrical content, what indisputably resounds about Emperor Tomato Ketchup is how compelling it is to listen to, even after a quarter-century on the shelf. The expanded edition of the album released in 2019 contains a bundle of demos and original mixes for most of the tracks, which make apparent the melodiousness at the core of Stereolab’s songwriting. Strip these songs to the bone and you’re still left with robust tunes: many of the album’s sturdiest hooks germinate from Gane’s scratchy guitar lines, which nicely frame the interplay of vocals from Sadier and Hansen. Hearing these tracks function in their basic forms confirms that Stereolab didn’t need great pile-ups of noise to suture their songs together: all was built on solid foundations, which were then pushed into thrilling new directions by the assembled collective.

Each song occupies its own self-absorbed space before the next bumps it (sometimes jarringly) off its perch. On ‘Cybele’s Reverie’, Sadier ponders what there is to do when we are no longer surprised by knowledge or novelty, wistfully reminiscing on the ravenous curiosity of childhood. Featuring a foregrounded string arrangement by Sean O’Hagan (which syncopates beautifully with the sprightly drum pattern), it’s a sumptuous song which is supplanted by the tumult of ‘Percolator’. Awash in acidic Moog notes, a gummy bassline, and building to a boiling point with a braying trumpet refrain, it’s the album’s busiest and most claustrophobic track, Sadier’s own mood reflecting the turmoil as she begins singing “j’ai très très peur ca c’est certain”. The jump from ‘Cybele’s Reverie’ to ‘Percolator’ is the most jarring shift in the tracklist, but it’s hard to see around any corners on Emperor Tomato Ketchup, which is constantly shifting in mood and attack. In its most immediate moments, you can hear Stereolab’s force as pop innovators, their polymathic grooves beckoning listeners to unexpected places. The title track comes closest to distilling as “classic” a Stereolab sound as can be anticipated from such a restless group: it’s a straight-up bop, the thick pulse of which has echoed through art-pop and alt-rock in the decades since. (‘Hey’ by Alvvays springs to mind whenever I hear those opening bars.) It’s followed by ‘Monstre Sacre’: the sparest and most disturbing song on the album, which features the kind of sawing strings that would have suited a Hitchcock psychodrama.

There are so many rooms to explore and details to get lost in, but the vitality of Emperor Tomato Ketchup is apparent regardless of how deep one chooses to dig into it. Just as ‘Metronomic Underground’ seems to create its own heat as it drifts towards its climax, the album likewise continues to produce its own strange energy. It’s widely hailed as one of Stereolab’s crowning achievements, though its follow-up – 1997’s Dots and Loops – is much more immediately appealing: smooth and tidy where its predecessor is fidgety and cluttered. Dots and Loops leans hard into the bossa nova stylings that the band had previously flirted with, and though the group remained admirably active and omnivorous until their 2009 hiatus, it’s these two albums which cast the longest shadows – over Stereolab’s work and beyond. Each presents a different side of the group with exceptional results, but Emperor Tomato Ketchup is the one that keeps drawing me back, into its tornado of musical creativity that refracts modern western existence back at the listener. The constant hum of urban movement, disillusionment and suspicion, pockets of surreal giddiness and chest-bursting excitement… It’s all mixed into Emperor Tomato Ketchup: a multitudinous album that’s constantly on the move, absorbing and reflecting all kinds of material in one dizzying trip.

21/02/21

25 More: And Their Refinement of the Decline

28/50

Stars of the Lid

And Their Refinement of the Decline (Kranky, 2007)

I spent six years of my twenties living in the same flat in Mornington Crescent, five of them with the same group of people. One evening during the final spring of my time there, as the four of us gathered to play a few rounds of The Mind, one of my flatmates cued up The Tired Sounds of Stars of the Lid. The album was chosen merely to provide some twinkling ambience for our pseudo-psychic gameplay, but I was captivated by the sounds issuing from the kitchen speakers: ambient music based around drones that were paradoxically both feather-light and heavy on the ears. (I can confirm that it works as a great soundtrack for The Mind.)

I favourited the album on Spotify, and started to play Tired Sounds and its successor [Stars of the Lid] And Their Refinement of the Decline as a sonic accompaniment for evening naps. This was in late April 2020, and London remained at a standstill as the UK’s initial national lockdown continued to stretch into the first glimmers of summer. In the evenings, I was physically tired from my day job (helping to source, pack and dispatch orders from a bookshop), and was emotionally stymied insofar as I felt unable to deal with the constant gushes of despondent global news. I couldn’t muster the psychological energy to confront and process the dizzying array of updates and sentiments jostling for my attention, and on numerous days I would get home from work, draw the blinds in my tiny room, and lie on my bed with the music of Stars of the Lid playing through my phone, letting the darkness thicken around me as I drifted in and out of sleep.

Brian McBride and Adam Wiltzie have been releasing music as Stars of the Lid since the early 1990s, but their final two albums (released in 2001 and 2007) are their most widely-celebrated works. The duo’s stock-in-trade is opaque minimalism, based around drones (sourced electronically, as well as from cellos, horns, harps, clarinets and more) that are held, sustained, and manipulated for minutes at a time. As with all drone music, what emerges from the constant ebb and flow of silence and noise are the textural and dynamic details teeming below the surface. Whereas I was first using the music to tune out, as I continued returning to the album with a snug pair of headphones, I became increasingly enchanted by its subtleties: the whorls and smudges of the sounds at play, and how the smallest adjustment in timbre or tone can send ripples through the whole. Tired Sounds and Refinement of the Decline each run to two hours in length, their vaporous tides washing through the listener, submerging them in the rise and fall of noise and articulating a density of sound that frequently arrives at profoundly affecting moments of beauty.

Both albums are incredible, but for me, And Their Refinement of the Decline has a greater emotional weight to it, which is in some way managed by the greater foregrounding of classical instrumentation. The results are highly expressionistic, teasing subjective emotional responses from the listener like a canvas of constantly shifting inkblots. The outlines of the music are simple, but the details within are abundant: very few individual elements are used, yet those in play are so texturally dense and contextually dynamic that significant emotional cues are drawn from seemingly unassuming moments. Entirely beatless and wordless (save for several sampled snippets of dialogue), the songs float with minimal context beyond their titles, and McBride and Wiltzie tease the listener by throwing the seriousness and sincerity of these into question. Cryptic and strangely beautiful names such as ‘Even if You’re Never Awake’ and ‘The Evil That Never Arrived’ are placed alongside workmanlike labels (‘Apreludes (In C Major)’) and jarring goofiness: ‘Dungtitled (In A Major)’ and ‘Dopamine Clouds Over Craven Cottage’. There’s a playfulness at work here, a reminder of the very earthy sources for sounds of such sweeping grandeur. The album even closes with a 17-minute opus called ‘December Hunting For Vegetarian Fuckface’.

As such, it is left to the listener to mine significance and meaning in these compositions, and what sounds desolate to one could seem hopeful and heavenly to another. Personally I find And Their Refinement of the Decline to be one of the most beautifully immersive and deeply sad albums I’ve ever heard: to my mind, this music articulates the sound of something ending, and disappearing – possibly forever. Listening to a track like ‘That Finger on Your Temple is the Barrel of My Raygun’ feels like watching something physical collapse in slow-motion, its materials disintegrating into dust, its attributes temporarily held in the mind as a mere echo, before it completely fades from all consciousness, consumed by a silence that is constantly alluded to and accentuated by the hum of rising and falling drones. (Because so many of these songs repeatedly lapse into near-silence, its genuine appearance feels substantial.)

I no longer reach for this album to serve as a napping companion, but I have come to associate it with the emotional impasse of my daily existence through this pandemic. As I write this, the UK’s third lockdown has been in place for just over a month, and I am one of the lucky people who has remained in relative comfort during the past year. I am still employed, I haven’t lost a close friend or family member to the virus, and more often than not, I’m sufficiently motivated to occupy myself through the otherwise static days with small tasks, hobbies and interests. Relatively speaking, I’m incredibly fortunate. But despite the distractions I give myself (in work, in projects, in escapism), an inescapable sense of sadness has been lapping at the edges of my consciousness since March 2020. It’s a natural result of such sudden and widespread upheaval, especially considering the fatal ramifications of the virus and its effect on an incomprehensible number of lives. At some point every day – separate from intentional check-ins with loved ones and news updates – my mind will tune itself in to this low-level hum of sadness, and lock into it for a time.

It’s in these instances that I wonder about the incremental – and possibly irrevocable – loss of things that we once took for granted: the small moments, experiences and feelings that shaped our lives before the pandemic took hold. Many routines and social traditions have receded into the distance, with some habitual behaviours completely abandoned, others shaken by new fears and concerns. The ongoing hope is that much of this – the “normality” we use as a means of contrasting the past with our strange present – has merely been put on hold. But there’s still no telling how many of these familiar ways and methods will return to us, nor when. If nothing else, the innocence and ignorance with which we went about our day-to-day lives before Covid-19 will never be completely restored. We flinch at television shows or films that feature crowds gathered without adhering to social distancing. We have become increasingly unmoored from communal environments – cinema screens, art galleries, pubs and cafés – that were once enjoyed so casually. Something as simple as hugging a friend in greeting or goodbye has become impossibly remote.

I feel as though I’m living in a state of glacial mourning, both personally and as part of a social collective. Many of us still default to dismissing our own psychological wellbeing, feeling that we ought not to complain about our lots when considered relative to the less fortunate. We remain silent for fears of causing offense, for showing our privilege, our ignorance and comparative fortunes. There is some validity to this, of course, and by the same token, it’s important to remain hopeful that better times will return, and with them many of the customs which we have dearly missed during this past year. But day by day and week by week, I feel further and further removed from the small moments that used to give shape to our daily lives. When my mind strays to dwell on such thoughts, they feel less like unpleasant intrusions than fleeting moments of cognisance. This low-level grief has been a constant presence throughout the pandemic, but for the most part, I keep it stifled in order to make do in the present.

Having returned to it consistently throughout the past ten months, And Their Refinement of the Decline has become something that I reach for when this type of quiet grief starts to become felt, when I can feel the sadness that we’re living with (and suppressing) starting to yawn right open. With its deliberate, mournful atmospheres, this album mirrors the internal weather I’ve been experiencing, the skeletal minimalism of these pieces tapping into immense swells of feeling. There’s a physical quality to this music, derived as much from the visceral nature of the sounds heard and the interpretive nature of the album’s lack of overt signifiers. Listening to them on headphones is like being dwarfed by a single mountain peak rising to a point on the horizon, or standing beneath a redwood tree towering into a fathomless white sky. When minor-key cello notes scythe slowly through ‘Articulate Silences Part 2’, the depth of the piece is completely transformed, giving the sensation of wading in water and suddenly finding oneself floating over a bottomless chasm.

In the foreword to her 1939 book Tropisms, Nathalie Sarraute described her fascination with – and attempts to represent in writing – the “movements, of which we are hardly cognisant, [that] slip through us on the frontiers of consciousness in the form of undefinable, extremely rapid sensations. They hide behind our gestures, beneath the words we speak, the feelings we manifest, are aware of experiencing and able to define”. Tropisms chronicles a series of disconnected moments in which the hidden truth of things is briefly, vertiginously visible beneath their given surfaces. In her writing, Sarraute captures and preserves these moments, and allows the reader to regard them by spreading them out “the same way a slow-motion film does”. In Sarraute’s writing, “time [is] no longer the time of real life, but of a hugely amplified present”.

Stars of the Lid do not communicate through the same medium or method, of course, but when listening to their music, I feel as though moments of reflection have been slowed and suspended, to be regarded at a glacial pace. Similarly to the work of Sarraute, And Their Refinement of the Decline amplifies these moments of deeply felt sadness, seeming to slow time to tease the tiniest sonic details from the sound of a single note being held or fiddled with. Its depth of melancholy parallels the sadness that I have been drawn to during this third lockdown, as a new year stretches ahead with no return to our past existence in sight, nor any true concept of when “normality” will be restored. We mourn the lost experiences of the past, in present moments that are themselves quickly extinguished by distraction, of turning back to the matters at hand: the business of living and making do for now.

And Their Refinement of the Decline has given dimensions to the melancholy of this period: when I sit with this music, I sit with the feelings of loss and longing that have been hovering at the back of my mind for the past year. On heavy afternoons, I still lie down to it, not to sleep, but to find an emotional analogue in its monumental string swells, sparkling tone clusters and lonely horn melodies. The entire two-hour experience is a consistently powerful one, but in terms of individual moments, ‘Even if You’re Never Awake (Deuxième)’ is the passage which I find most moving of all. The rising and falling notes it begins with are redolent of revolving lighthouse beams, before further elements deepen and transform the mood of the piece. Three minutes in, a short and lonely string refrain softly sounds through a thick veil of fog, before wave upon wave of majestic string surges break over the song, softly punctuated by flickering effects that play like shards of light on one of Turner’s masterpieces. It’s reductive to simply try to describe it, but ‘Even if You’re Never Awake (Deuxième)’ contains all that I love about And Their Refinement of the Decline within ten minutes of sublime power and grace. It is my key to the album: a surrender to an internal landscape of feeling, a present moment stretched to fill every horizon, in which I consider and mourn for aspects of a past that have disappeared from our lives – for now, if not forever.

07/02/21

25 More: We Got It From Here… Thank You 4 Your Service

27 / 50

A Tribe Called Quest

We Got it From Here… Thank You 4 Your Service (Epic, 2016)

At the end of ‘Push it Along’ – the opening track on A Tribe Called Quest’s 1990 debut – Jarobi White introduced the four members of the crew: his “right-hand man” Phife Dawg, “sound provider” Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and “top of the pyramid, the leader,” Q-Tip. (Jarobi pegged himself as “the mystic man”, and has since been identified as the “spirit” of the group by Q-Tip and others.) It’s certainly an accurate reflection of Tribe’s dynamic during the first leg of their journey: Q-Tip the central visionary, his controlled cool complemented by the excitable everyman appeal of Phife Dawg at his side. Muhammad brought up the beats, providing Tribe with their backbone of expertly-assembled samples. The amicable Jarobi brought humour and energy to the creative sessions, keeping the vibes positive and providing a diplomatic buffer between his companions whenever the need arose.

21 years after the release of Tribe’s first album, Michael Rapaport’s revealing documentary Beats, Rhymes and Life: The Travels of A Tribe Called Quest featured footage of Q-Tip during a particularly heated moment after a 2008 reunion show, repeatedly insisting that Tribe was never about individual spotlighting or ego. “It’s about Tribe, it’s about the fucking unit,” he emphasised. The notion of collectivism within the group was heavily scrutinised in the documentary, especially in interviews with Phife, who claimed to feel an increasing sense of creative dictatorship from Q-Tip as the 1990s progressed and tensions escalated. In their work following 1993’s Midnight Marauders, Phife asserted that “the chemistry was dead” between the crew members, especially as the presence of new collaborators and co-producers steered Tribe’s sound down different (and not always warmly-received) avenues.

It’s true that A Tribe Called Quest was a consistently fluid unit. Q-Tip was certainly “top of the pyramid” throughout their run: the man with ambitious creative visions, and the capacity to rally others in service of attaining them. Phife, who only featured on four of the debut’s fourteen cuts, would only become a consistent tag-teamer with Q-Tip on 1991’s The Low End Theory, and even then would need to be coaxed into the studio, often penning his bars while riding the train to get there. Muhammad’s role as “sound provider” was in flux from 1991 onwards, ceding ground to Q-Tip (himself a versatile producer and beatmaker), while Jarobi made no appearances on Tribe’s recorded work for more than two decades after the release of People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm.

And yet, throughout the group’s lifetime, no matter the context of recording or number of shifts in creative input, as Q-Tip stressed in Beats, Rhymes and Life, “the shit said ‘Tribe’”. The flag remained planted, advertising the same group listeners had always known (or thought they knew). Even when core members weren’t involved, when collaborators and credits rotated, when the organisation of the unit was a world away from the dynamic touted by Jarobi on ‘Push it Along’, there was some kind of alchemy at work: the spirit of the group could be heard and felt. No matter the interpersonal frictions and stylistic modifications, A Tribe Called Quest could be recognised, even if only in glimmers through the diminishing returns of their late-90s output. What is most miraculous of all is that on Tribe’s final album, released a full 18 years after the group’s split in 1998, you can hear – with delight, and without reservation – the same energy, spirit and verve that was captured so well in their three classic original records. We Got it From Here… Thank You 4 Your Service is a resoundingly powerful farewell from a seminal group, still armed with so much to say, and delivered with mastery.

In March 2016, Phife Dawg died due to health complications associated with his diabetes. Following this gut-punch, it was revealed that at the time of his death, Phife had been working with Q-Tip, secretly preparing the first Tribe album since 1998’s The Love Movement, and the last of their six-album contract with Jive Records. Work on the album was only partially complete, but even so, Phife appeared on eight of the final sixteen tracks, and his verses contain a palpable sense of renewed excitement and reconciliation in his partnership with Q-Tip. Jarobi was also back and woven tightly into the fold, appearing often and sparring seamlessly. Of the original four, only Muhammad was unable to join, due to conflicting commitments working on the Luke Cage soundtrack. As before, so it was again: a new Tribe album, completed without all original members present for its creation. But blessedly, We Got it From Here makes good on Q-Tip’s words in the documentary: this is an album that captures the undeniable, alchemical spirit of Tribe, and goes one further by capturing the group sounding tighter than ever before. The lyrics are sharper, the instrumentals thrillingly diverse, the performers so tightly enmeshed that their chemistry borders on inebriating.